Art institutions around the world are celebrating the 150th anniversary of Impressionism, which staged its first exhibit in April 1874, and curators are seizing the opportunity to dig further into the lesser-known aspects of the movement, notably the historically overlooked women artists from the period. Fresh looks at women Impressionists are underway or upcoming at the National Gallery of Ireland, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Musée de Pont-Aven in France, the Museum der bildenden Kunste (MdbK) in Leipzig, and elsewhere around the world.

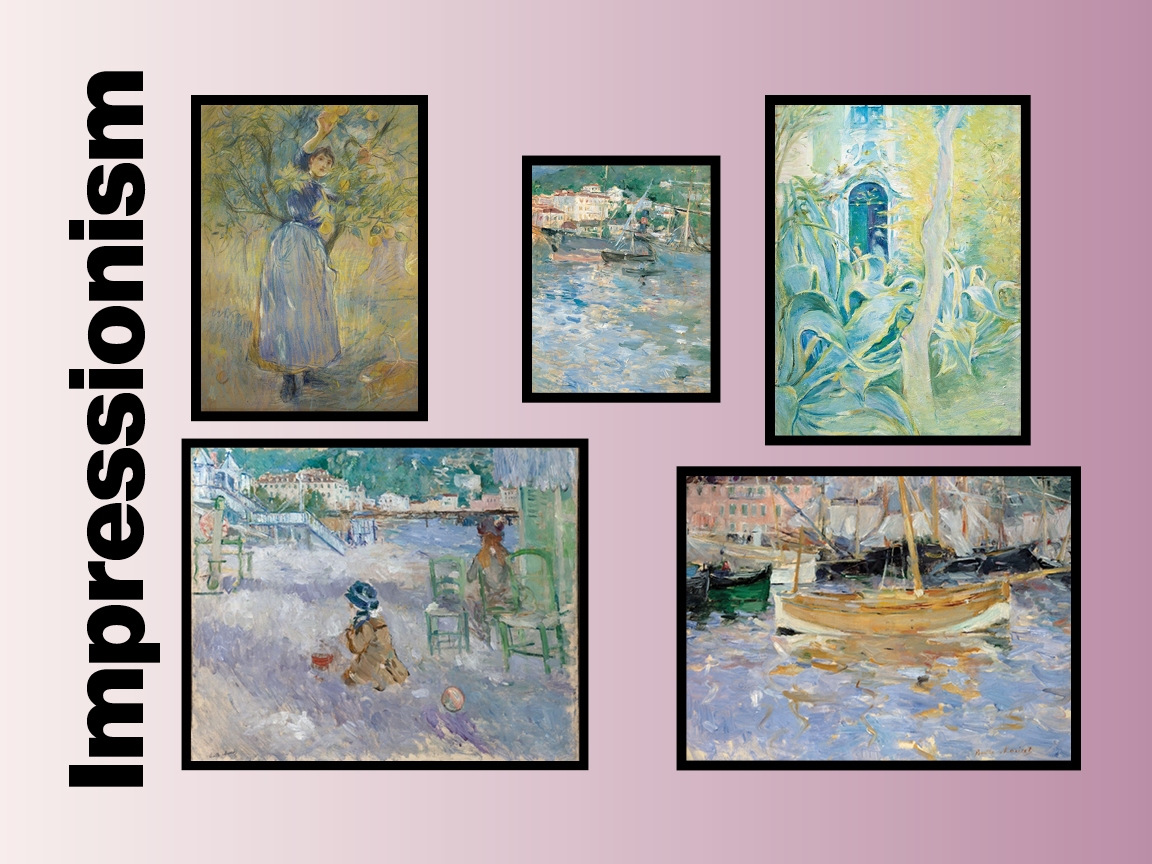

One particularly intriguing example is the forthcoming show “Berthe Morisot à Nice, escales impressionnistes,” (“Berthe Morisot in Nice, an Impressionist Stopover”) at the Musée des Beaux-Arts Jules Chéret in the seaside city, which runs June 7 through September 29. It will travel to Genoa’s Palazzo Ducale Fondazione per la Cutura afterward. Morisot (1841–1895) was a central figure of Impressionism; she exhibited in seven out of eight of the movement’s shows, including the first one. Yet still today, when most think of the founders of the movement, few mention Morisot. The Nice exhibit attempts to correct the record by showing not only paintings she created there but also works by women in her Riviera circle.

With about 60 artworks by Morisot related to the wintry periods she spent in Nice in 1881–82 and 1888–89, complemented by around 40 pieces by other women artists, the exhibit is among the first to recognize the breadth and wealth of the feminine art scene in Nice at the time. In fact, one of the show’s curators told ARTnews that in conducting new research into the museum’s own under-examined collection, they discovered that no fewer than about 650 women were making art professionally in the region during the Belle Epoque, between 1877 and 1914. These women came from all over, representing some 20 nationalities.

“While we were researching more about Berthe Morisot and her period, we realized hundreds of women exhibited in Nice’s salons, gave art classes, or simply worked on the French Riviera,” said Johanne Lindskog, director of the museum and cocurator of the show. “It’s crazy, actually, and a spectacular quantity, which has allowed us to reestablish a certain historical reality about the presence of women in [the] Riviera’s art scene.”

These artists included the better-known Eva Gonzalès (1849–1883), who studied under Édouard Manet, Marie Bashkirtseff (1858–1884), Louise Breslau (1856–1927), and Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), as well as artists whose names are less familiar: Thérèse Cotard-Dupré (1877–1920) and Alice Vasselon (1849–1893). “And, of course, they all knew each other and Berthe Morisot, either because they exhibited together or were in the same network,” Lindskog said.

Why were so many women making art around Nice and nearby environs like Cannes and Monaco? Perhaps following the example of Paris’s Académie Julian, which accepted women, art ateliers for women began to pop up, run by the likes of Jean-Jacques Henner, who encouraged his students to work and exhibit in Nice. In this cosmopolitan southern French city, women found a thriving art market and patrons who supported them. Moreover, the French Riviera, with its pictorial landscapes, was near Italy, where artists traditionally went to study classical and Renaissance art. Finally, many of these women painters themselves came from relative wealth and had second homes near the coast, an area prized for its warm weather and related health benefits. These women of means depended a little less on their husbands and fathers and were freer to explore their personal and artistic interests.

They also made work in a variety of styles that often dipped into, or was in dialogue with, the “new painting” that was Impressionism. Breslau, for instance, is known for her naturalistic realism but occasionally showed the influence of the Impressionists, whom she knew—notably Edgar Degas and the important Impressionist dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. “There’s a crisscrossing of painting that comes in contact with Impressionism, and hybrid works that are not entirely one or the other,” Lindskog noted.

The curators hope to underscore the hybridized aspect of the art made at the time, favoring a less rigid depiction of Impressionism and the context from which it sprang—an approach also seen in the blockbuster Impressionism exhibit currently at Paris’s Musée d’Orsay, which emphasizes Morisot’s participation. “Museums have tended to favor a thematic, chronological approach, which has given the public the false impression that events occur[ed] in a segmented manner, one after the other,” said Lindskog. “Our wish is to reestablish a certain historical accuracy around what people saw at the time and what interested them. What are the points of contact and associations? It’s this complexity that is interesting.”

In their research, curators including art historian Marianne Mathieu also came across new evidence contradicting the belief that all Impressionist painting was executed swiftly. Mathieu and Lindskog found that Morisot would spend long periods in her studio preparing her final paintings, and that she made relatively few “final” works, suggesting she could take her time, given her financial security. In addition, Lindskog said colleagues discovered previously unknown artworks by Morisot’s husband, Eugène Manet, who was her informal dealer and production assistant, as well as by her daughter, Julie Manet. It would appear that the family painted together, often following Morisot’s lead and replicating her compositions.

As curators “begin to research Impressionism in alternative ways to simply lining up masterpieces along a wall,” Lindskog said, they continue to discover new information about the lives of the artists, which contributes to what we know of as Impressionism. “As we look closer at the real conditions in which these artworks were created, with a more social approach . . . we inevitably discover people and participants that we hadn’t noticed until now.”