This year marks the 50th anniversary of Pablo Picasso’s death on April 8, 1973, at age 91. He died in Mougins, France, at his hilltop villa, a 35-room mansion surrounded by 17 acres adjacent to the chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Vie—a site that, until the 18th century, had served as a sanctuary for families from the region who came to have their stillborn children baptized.

The estate, located not far from Cannes on the French Riviera, was one of many expansive properties owned by Picasso that attested to the fame and fortune he’d accrued over a legendary 70-year career. But another salient feature of Picasso’s life took form in the woman who stood by his bedside that day: his second wife, Jacqueline Roque, who was 45 years his junior. The age differential was typical of Picasso’s relationships with the scores of women he’d bedded, taken as mistresses, fathered children with, and been prone to emotionally abusing.

Today Picasso’s reputation as a womanizer and sexual predator has clouded his legacy as the colossus of 20th-century art, the explosive figure who birthed modernism and created the template for the artist as a superstar whose brilliance excuses all manner of sins. That attitude hasn’t aged well, and neither has the misogyny that percolates throughout Picasso’s work. In this respect, he was hardly alone among the men of his generation, but his views on women were coarse even for the standards of the day. “There are only two types of women,” he once said, “goddesses and doormats.” His thoughts on matrimony were just as unenlightened, and even violent in tone: “Every time I change wives, I should burn the last one. . . . You kill the woman, and you wipe out the past she represents.” Still, the women in Picasso’s life played a huge role in his art, as muses and as subjects who both fascinated and terrified him.

To borrow a phrase that film critic Pauline Kael bestowed on the British actor Bob Hoskins, Picasso was “a testicle on legs,” a man whose appetites were as prodigious as his artistic production. And therein lies the rub: To celebrate Picasso, you must separate the artist from his art, a tall order given how canceled he’d be if he were still with us. Yet his achievements are so overwhelming that to ignore them or his life would amount to willful blindness.

Read Part 2: 1920s to 1970s here.

-

Early Life

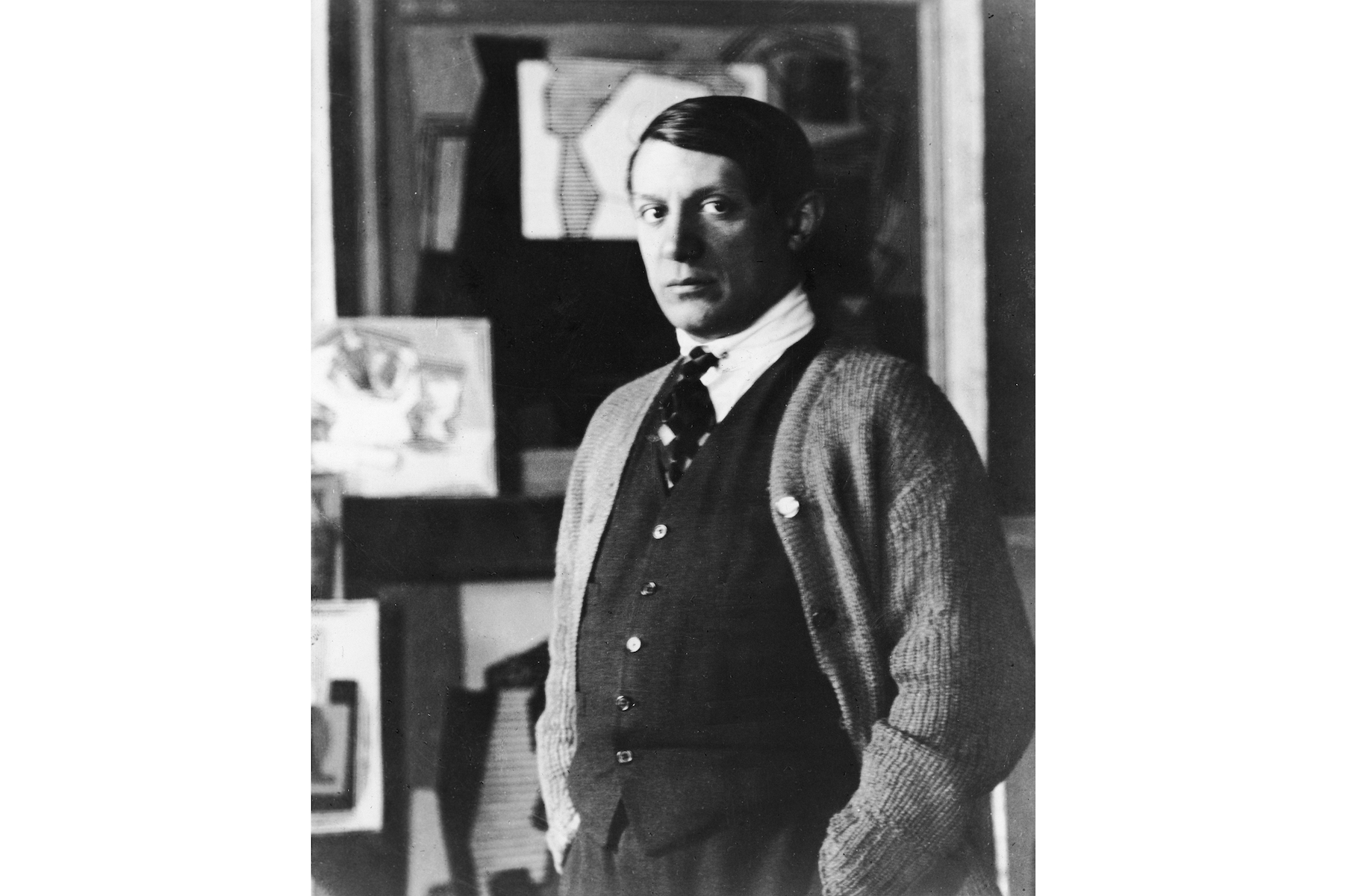

Image Credit: Picasso Museum, Paris/Wikimedia Commons Picasso was born Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Crispiniano de la Santísima Trinidad on October 25, 1881, in the southern Spanish city of Málaga. He was called Pablo Ruiz Picasso after his father, Jose Ruiz Blaso, and his mother, Maria Picasso Lopez. In time he dropped his middle name to assume the moniker that became synonymous with genius.

Picasso’s father, a professor of art at the Malaga School of Fine Arts and curator of the local museum, was a painter known for avian studies, particularly of doves, so in a sense young Pablo went into the family business. From an early age he demonstrated an aptitude for art well beyond his years, though little else in terms of study since he was dyslexic at a time when its diagnosis was unknown.

He was often sent out of the classroom as punishment for being a poor student, providing opportunities for him to sketch in his notebook. It’s reasonable to assume his struggles with reading shaped his art, but not in the way one might think, even if he did sometimes render images upside down or backwards; it’s likely that his disability sharpened his visual acuity as a form of compensation.

Picasso received training in drawing and painting from his father, becoming so adept that he was admitted at age 11 to the School of Fine and Applied Arts in La Coruna, Spain, a town his family had moved to in 1892. By age 13 he had produced his first oil paintings, which he began to exhibit and sell.

-

Barcelona

In 1895 Picasso’s family suffered a trauma when his seven-year-old sister, Conchita, died of diphtheria. Not long thereafter, the family moved to Barcelona, where Picasso’s father had taken a position at its School of Fine Arts. Ruiz persuaded the admissions committee to allow his son to take its entrance exam; Picasso needed only a week to complete a process that usually required a month, and so, aged 14, he entered the academy.

Picasso thrived in Barcelona and came to consider the city his hometown. There he mingled with the local avant-garde circle at its favorite watering hole, the café/bar known as Els Quatre Gats (The Four Cats).

-

Madrid

In 1897 Picasso’s father and uncle decided to enroll him the country’s most prestigious art school, the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid. His acceptance at the age of 16 was no surprise by then, but he tired of attending classes and began to skip them.

Instead he imbibed the collections of Old Masters at the Prado and elsewhere in the Spanish capital, familiarizing himself with the work of Velázquez, Rembrandt, and Vermeer. He became especially enamored of Caravaggio and El Greco. The latter in particular had a profound effect on the young artist; indeed, the compositional grouping of El Greco’s Vision of Saint John (1608–14) would, a decade later, directly influence Picasso’s history-shattering painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), one of several Picasso compositions that owed a debt to the Greek Old Master.

-

Early Painting

Image Credit: Eduard Vallès Archive, Barcelona Picasso’s ambitions would naturally take him to Paris, and in 1900 he traveled there with his friend, fellow artist, and countryman Carles Casagemas for a two-month stay. In one of the works he created there, Le Moulin de la Galette (1900), Picasso takes a Belle Epoque nightlife scene and gives it a brooding Spanish twist by casting a dark shroud of chiaroscuro over a crowd in a bar.

The figures and their faces are blurred, imparting a spectral quality to a group dancing in the background as well as to a trio of seated women foregrounded in the lower left-hand corner. One of them, cropped nearly out of the frame, leans with her elbow on a table, offering a sly smile and sidelong glance to someone outside the scene. She’s Germaine Gargallo, an artist’s model Casagemas fell madly in love with—so much so that when his passion went unrequited, he put a pistol to his head.

Picasso immortalized Casagemas’s desperate act with a closeup portrait of his dead friend in repose (The Dead Casagemas, 1901), the gunshot wound on his temple clearly visible. Gargallo would later become Picasso’s mistress.

-

Paris

Image Credit: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images via Getty Images Over the next several years, Picasso migrated between Madrid, Barcelona, and Paris before permanently settling in the City of Light in 1904. During this period, he met the poet and artist Max Jacob (1876–1944), and the two formed the first of several key relationships in Picasso’s life.

Jacob was a French Jew, a homosexual with a predilection for policemen who would later die in a Nazi concentration camp just outside Paris. Jacob taught Picasso to speak French, and they shared a room on the Boulevard Voltaire, where they lived in a state of poverty so abject that they sometimes burned paintings for warmth. More significantly, Jacob introduced Picasso to the poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, who in turn introduced him to Georges Braque, the painter with whom Picasso would eventually form the most consequential partnership in modern art.

Jacob, Apollinaire, and Braque formed the nucleus of “la bande de Picasso,” a gang of likeminded artistic rebels centered on the charismatic Spaniard. The group was known for its rowdiness and its disregard for public decorum, which expressed itself in wild antics, like the time Picasso fired a pistol over the heads of a group of Germans pestering him outside the famed Lapin Agile café. La bande’s anarchic reputation was such that when the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre in 1911, Picasso and Apollinaire were considered suspects, though they had nothing to do with the robbery.

Nonetheless, Picasso’s work drew attention from the start. His earliest paintings in Paris married Charles Baudelaire’s diktat to “paint modern life” with the dreamlike intrusions of Symbolism.

-

Blue Period

Image Credit: Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Sylvie Chan-Liat Casagemas’s demise led Picasso to his first truly mature style: his Blue Period paintings, created between 1901 and 1904, in which the artist reduced his palette to a near-monochromatic scheme. “I started painting in blue when I learned of Casagemas’s death,” Picasso later recalled, though art historians also attribute the artist’s decision to a bout of depression brought on by his impoverishment at the time.

Reflecting his own marginalization at the beginning of his career, Picasso turned to society’s outcasts for subject matter: beggars, prisoners, prostitutes, and the blind, all set in compositions infused with Catholic symbolism. Much as he would do a few years later with Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Picasso conducted fieldwork, seeking inspiration.

A visit to a women’s prison hospital run by the Church, for example, resulted in L’Entrevue (1902), a painting of two rather despondent looking nuns. El Greco’s attenuated figuration and penchant for imparting a bluish tint to human flesh is evident not only in this work, but also in Blue Period icons such as The Old Guitarist (1903), in which the titular figure seems bent over his instrument by the weight of his immiseration.

-

Rose Period

In 1904 Picasso entered his Rose Period, so called because his color scheme became dominated by variations of red, orange, and pink, though he also employed blue, yellow ocher, and other colors. Content-wise, circus performers took the place of the destitute, and while one can surmise that Picasso had taken a cheerful turn chromatically and thematically, the acrobats, clowns, and trapeze artists inhabiting these paintings generally wear grim expressions.

It’s also the case that the circus traditionally served as a safe harbor for social misfits, so one could argue that the difference between Picasso’s Blue and Rose Periods was a matter of degree rather than kind. While he dispensed with the gloomy hues of the Blue Period, his Rose Period paintings retained El Greco’s elongated anatomy; in one case, Boy Leading a Horse (1905), Picasso took a page from the former’s Saint Martin and the Beggar (1597–99), with each featuring a nude or barely clad figure walking beside a horse.

Picasso’s interest in the circus stemmed from his frequent attendance at the Cirque Medrano alongside Braque. One figure who repeatedly shows up in Rose Period scenes is the commedia dell’arte character Harlequin; known for his distinctive diamond-patterned costume, he appears in such compositions as Family of Saltimbanques and Harlequin’s Family (both 1905).

Whatever else one could say about Picasso’s Rose Period, it’s true that his emotional state had improved. Some have attributed this to two events in his life: the setting up of his first proper studio in Paris at the Bateau-Lavoir building in Montmartre (the only place, Picasso would later recall, where he was truly happy); and the onset of his relationship with Fernande Olivier, a French artist and model with whom he had a turbulent, jealousy-riven relationship for seven years. She was also the first woman to play the role of Picasso’s muse, as testified by the 60 or so portraits he made of her.

-

1906: A Year of Transition

Image Credit: AFP via Getty Images In 1906 Picasso wound down his Rose Period with two portraits—one of the American expatriate Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) and another of himself as a smooth-faced young artist with palette in hand. In the self-portrait, he wears a contemplative expression, his eyes gazing out of the picture as if sizing up a brighter future. In fact, both paintings mark a turning point in his artistic direction and personal fortunes.

Stein was a novelist, poet, playwright, and—most important for Picasso—an avid collector of avant-garde art. The youngest of five children, she was born into a wealthy Jewish family near Pittsburgh. She had the means to become a key patron for Picasso, which improved his lot considerably.

Stein shared a two-story apartment with her brother Leo, at 27 Rue de Fleurus on the Left Bank, where she held weekly salons attended by a who’s who of artists and writers from Europe and America. Picasso met her in 1905, and by most accounts she was one of the few women he respected. The heavyset Stein was formidable not only physically but intellectually, and she shared with Picasso an ambition to go down in history—as, of course, they both did.

Picasso and Stein, then, were well matched, so it’s no wonder that he asked if he could paint her portrait. Stein agreed and would later recall that it took some 80 to 90 sittings, with Picasso becoming so frustrated at one point that he painted out her head. After some time away from the piece, he completed it in 1906 without his subject being present.

Stein is seen seated and leaning slightly forward. Picasso appropriated the pose from Portrait of Monsieur Bertin (1832) by the great neo-classicist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867), which Picasso had seen at the Louvre. A wealthy art collector and newspaper editor with royalist sympathies, Bertin possessed the same imposing bulk as Picasso’s Stein, and like her, he is settled in a chair with his hands on his thighs.

By this time, Picasso’s penchant for unapologetically raiding the compositional pantries of other artists had become obvious. “Good artists borrow, great artists steal,” he purportedly remarked, and in this respect his greatest theft lay ahead with the most important painting of his oeuvre, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

-

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon

Completed during the summer of 1907, Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon represents the ur-painting of modern art, and it was arguably born of two places: Picasso’s studio and the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro. On a visit to the museum while working on Les Demoiselles, Picasso saw a group of tribal masks expropriated from France’s colonies in Africa. Thanks to them, Les Demoiselles turned out quite differently from the painting Picasso had planned.

Les Demoiselles is set in a bordello on a street in Barcelona’s red-light district where Picasso once had a studio. It depicts a group of five female nudes (one of whom was modeled on Fernande Olivier), prostitutes who are parading their bodies for customers. In his original studies, Picasso had included two men, one of whom he described as a medical student in his notes. After Picasso’s tour of the Trocadéro, however, they were elided, and the faces of three of the women were altered to resemble the ritual artifacts Picasso had encountered.

Les Demoiselles’s palette combines the hues of Picasso’s Blue and Rose Periods, while its paint handling owed an obvious debt to Cézanne. More important, Picasso extrapolated the latter’s brushwork into triangular and rhomboid configurations that defined both figure and ground. Gone was any sense of perspective: A still life atop a table appears as a flat plane near the bottom of the image, while a masked woman at the lower right has her back turned toward the viewer as her head twists around at an impossible angle.

-

The African Period

Though Les Demoiselles is thought of as the first Cubist painting, it was Picasso’s initial foray into what became known as his African Period, which lasted until 1909. Besides visiting the Trocadéro, Picasso had started collecting African art around the time he worked on Les Demoiselles, and in the three years following that painting, he produced a body of works that were even more Africanized.

Among these were portraits—including one of himself—and studies of female nudes. (Picasso wasn’t alone in grazing from the buffet of cultural imperialism; Matisse too was entranced by African objects, echoes of which found their way into his art.) By 1909, however, the overt influence of African art on Picasso began to wane as he shifted his approach once again, this time in a direction galvanized with the help of his friend Braque.

-

Picasso and Braque

Georges Braque (1882–1963) was born in Argenteuil, near Paris, but grew up in the port city of Le Havre on the Normandy coast. His father and grandfather were house painters and decorators by trade, and he was expected to follow suit.

But while training to do so, Braque studied art in the evenings, and he eventually wound up at the Académie Humbert in Paris. Temperamentally, Picasso and Braque were diametric opposites, but somehow the former’s volatile personality and the latter’s reserve mixed to create the art-historical combustion that was Analytic Cubism.

-

The Birth of Cubism

The year Picasso painted Les Demoiselles, Braque paid him a visit at the Bateau-Lavoir. Braque had been associated with the Fauvists, but the sight of Picasso’s triumph shook him, and so he joined Picasso in elaborating on the tropes in Les Demoiselles over the next four years, launching Analytic Cubism in the bargain.

Both artists committed themselves to their joint enterprise to such an extent that a painting by one artist was not considered finished until the other signed off on it. It’s no wonder, then, that their canvases become nearly indistinguishable, or that Braque compared their collaboration to a pair of “mountain-climbers roped together.”

Concentrating mostly on still lifes, Picasso and Braque forayed into near abstraction, collapsing figure and ground into planar configurations that occupied the same compositional strata, eliminating the perception of depth. Objects were depicted from different angles simultaneously, often in shifting patterns meant to suggest the movement of the eye over and around a subject. Rather than rendering something from a particular vantage point in static terms, Cubism evoked the kinesthetics of seeing.

More significantly, however, Braque invented collage, for which he pasted bits of newsprint and wallpaper on his canvases. A kind of meta-commentary on the trompe l’oeil genre, this simple gesture proved to have a profound effect on 20th-century art by narrowing the gap between art and life and instigating a plethora of appropriative strategies to come.

-

Synthetic Cubism

Image Credit: AFP via Getty Images By 1914 Picasso and Braque had exhausted Analytic Cubism’s potential and transitioned to a variation dubbed Synthetic Cubism. While the casual viewer might be hard pressed to tell the two approaches apart, they diverged significantly.

For Analytic Cubism, the two mountain climbers had limited their palettes largely to subdued browns, grays, and blues, as both at this point were more interested in reeducating the eye than in pleasing it. With Synthetic Cubism, brighter colors were introduced, textures were added (with collage playing a part), and compositions became flatter and less busy.

-

Picasso and Sculpture

Though he’s known for his paintings, Picasso maintained a concurrent sculptural practice that proved just as consequential for 20th-century art. In 1909 he created a portrait bust of Fernande Olivier in a style that seemed midway between his African Period and Analytic Cubism.

In terms of sculptural technique, however, the piece was quite conventional, as it was modeled out of clay. Interestingly, Picasso had no formal education as a sculptor, which ultimately proved to be a benefit, since he was free of preconceived notions about working three-dimensionally. And so, in 1912, he fashioned Guitar, a piece that did for sculpture what Les Demoiselles had done for painting.

Made of cardboard, twine, and wire, Guitar was pasted and strung together as a series of flat shapes that rendered its subject whole even as it seemed to be coming apart. A translation of Cubism into physical space, Guitar wasn’t wrested from solid material but rather assembled from parts, marking a tectonic shift in how sculpture was made.

Similarly, Glass of Absinthe (1914) had far-ranging effects. Though it was solidly cast in bronze, Picasso affixed as a final touch an actual absinthe spoon (the flat, slotted utensil holding a lump of sugar, over which the liquor was traditionally poured). This gesture wound up introducing a whole genre of found-object art.

-

A Chapter Closes

Image Credit: Albert Harlingue/Roger-Viollet/Getty Images By the start of the 1920s, Picasso had become internationally famous, standing between the end of one era and the start of another. He was no longer the impecunious rebel tearing up Montmartre with his gang, and key friends from that time were gone. Apollinaire, who’d served in World War I on the Western Front, died of the Spanish flu, while Jacob converted to Roman Catholicism and decamped for a Benedictine monastery in the Loire Valley.

Picasso immortalized their absence in his Synthetic Cubist masterpiece Three Musicians (1921). Comprising a pair of collage and oil canvases, Three Musicians signaled a return to the commedia dell’arte theme of the Rose Period, with Picasso depicted as Harlequin playing a guitar; Apollinaire as Harlequin’s commedia foil, Pierrot, playing a flute; and Jacob attired as a monk holding sheet music.

In two decades, Picasso had utterly transformed art, and Three Musicians is undoubtedly a nostalgic reflection on those years. What he couldn’t know was that another half century of work lay ahead of him.